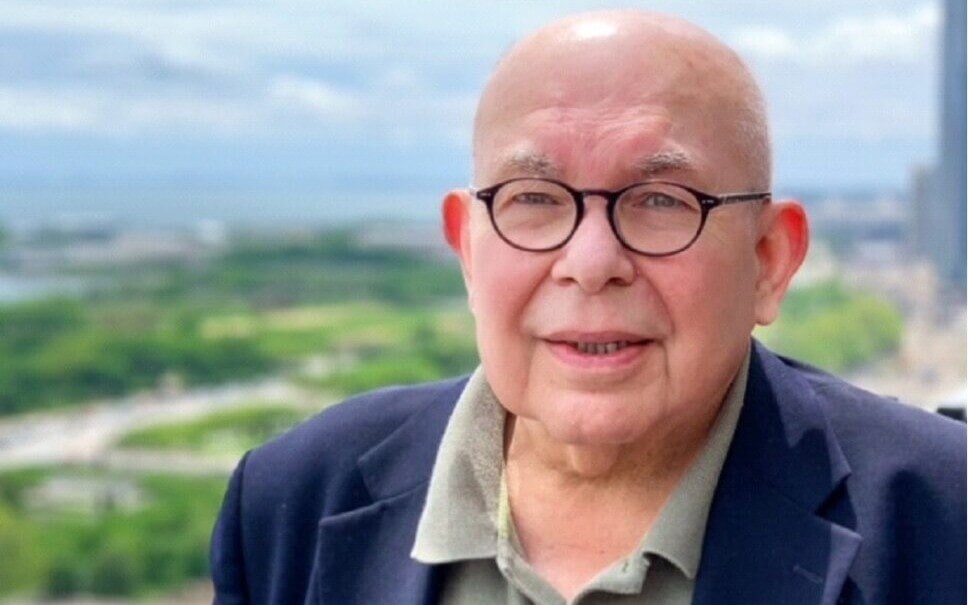

Growing up in the Chicago suburb of Skokie in the 1950s, Peri Arnold never envisioned a 50-year career of teaching and social justice activism. But it wasn’t until attending Roosevelt after an unsatisfying state school college experience that the University “changed [his] life.”

“I grew up in a leftist family and was fairly politically engaged from a young age, and so I was aware of Roosevelt in Chicago and its reputation for inclusive and progressive policies,” he says. “But it wasn’t until I attended and realized my passion for being a proper student and teacher.”

Arnold would go on to an immensely successful career as a professor at the University of Notre Dame, author of multiple history books and education reform activist in the Indiana prison system, but it was his undergraduate experience at Roosevelt that compelled him to approach academics with a social justice lens. A self-proclaimed “terrible and directionless student” in high school, Arnold credits two Roosevelt instructors in particular—academic advisor Martin Dubin and British historian Paul Johnson—for demonstrating how to integrate primary sources, contemporary world events and an engaging lecture style into classes that stress how the past can inform current decisions. Combined with a campus atmosphere focused on progressive issues during the politically turbulent 1960s, Arnold discovered his interest in political science.

“Attending college during that era really informed my political lens and opened the doors to so many viewpoints,” he says. “The demographics of Roosevelt were unusually diverse for the 1960s, and so I made friends with people from so many different racial and ethnic backgrounds. And attending school in the heart of downtown during the 1960s exposed me to so much groundbreaking art and music. We were blocks from the Art Institute and Symphony Center, and I would constantly try to see new exhibitions and works.”

After graduating with a bachelor’s in political science, Arnold would continue his education and eventually earn a master’s and doctorate from the University of Chicago before joining the faculty at the University of Notre Dame. He was the first ever Jewish professor to serve on the political science department of the famously Catholic university, and he brought the Roosevelt philosophy of inclusivity to his work by serving on search committees to expand and diversify the faculty.

Arnold would also find success as a published author in 1987 with Making the Managerial Presidency, which won the Brownlow Book Award of the National Academy of Public Administration. The book focuses on the slow consolidation of power by the executive branch throughout the 20th century, and how presidential decisions can increasingly overpower the legislative branch. He also later wrote Remaking the Presidency: Roosevelt, Taft, and Wilson, which focused on how presidents during the Progressive Era of the early 20th century worked at cross purposes to both improve bureaucratic functions and centralize power in the executive branch.

Although he retired from teaching in 2015, Arnold continues to live out the guiding Roosevelt principles of inclusivity and educational accessibility. His current research focuses on ethnic communities and political leadership in the consolidation of Chicago's Democratic machine, particularly amongst Russian and German Jewish communities during the 1920s and ‘30s. And he also established a program to teach incarcerated individuals at the Westville Correctional Center in Indiana.

“We were inspired by a program established by Bard College in New York state, and they came to Indiana to provide a course infrastructure for us,” he says. “Soon, we had a significant prison population that was reading Plato and determined to advance their careers once their sentences were up.” The program soon flourished to include a dedicated college dormitory in the prison, and it earned the certification to grant associates degrees to inmates. Arnold remains immensely proud of the program, and he still travels to the prison regularly to teach political science and history classes.

“Being formally retired doesn’t mean I ever want to stop learning or teaching,” he says. “For those who have dedicated their lives to this area of study, our work should never stop.”