Juneteenth arrives during a national conversation about the future of social justice in the United States. To commemorate the holiday, Roosevelt University professor Natasha L. Robinson, Esq., writes about its history and meaning today.

Robinson is a lecturer in the Government, Law and Justice department. She has been a licensed attorney specializing in criminal defense for 20 years, working as an assistant public defender for the Law Office of Cook County Public Defender for 12 years.

What is Juneteenth?

Juneteenth commemorates the celebration of enslaved African Americans in the state of Texas learning of their freedom being provided to them on June 19th, 1865, more than two and a half years after slavery had been officially ended by the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863.

Juneteenth is also called “Freedom Day” and “Jubilee Day” as the state of Texas was one of the last areas in which the official notice of emancipation had yet to reach those Blacks who had been enslaved.

Why do we celebrate Juneteenth?

It is important to note that, firstly, the legacy of Africans in America does not begin in slavery on these American shores, but on the shores of West Africa, through the hearts and minds of kings, queens, teachers, doctors, healers, fighters, advocates, chemists, mathematicians and the like.

It is through their fight to survive and thrive through the Maafa, the Transatlantic Slave Trade, and their being kidnapped, raped and pillaged that their lineage, their descendants, built this country with the toil of their hands, despite being disregarded and disrespected by society, the law, politics and their fellow citizens. They fought for a country that did not fight for them, and learning that they would no longer be enslaved as property began the journey of being empowered as a people.

It is important to celebrate Juneteenth to remember the story and to share the story with everyone as it is a painful but necessary narrative to share.

What does Juneteenth mean in 2021?

I see the relevance of this holiday in the 21st century as a call to our country to remember, to re-member and to reform. The injustices of our criminal justice system are related to the enslavement of my people, Africans in the Diaspora. While slavery as an institution has ended, the remnants of enslavement still remain in weaponized discretion used by police officers, prosecutorial misconduct, defensive tactics that offer more oppression than liberation, judicial sentences that disproportionately punish those involved in the criminal legal system based on race and class rather than the alleged criminal misconduct, and the enslavement-like correctional systems that house persons in jails and prisons. Furthermore, the laws of our city, state and nation need to be created in a way that establishes reform rather than continuing to marginalize Black citizens.

In this 21st century, we need to admit that our country loves history, but fails to embrace progress. Progress means recognizing that in this 21st century, lynching can be literal and figurative, from the physical hanging of Black bodies in trees, to the proverbial hanging of Black students and their voices when they are told they are too strong, too vocal, too angry, and then their actions and voices are silenced and sacrificed on the altar of academic privilege and protocol.

We need to remember and re-member who we all are, to bring ourselves back to ourselves, and in the spirit of Ubuntu, understand as we reform our society, know that "I am because we are, and because we are, I am."

As long as there are policies and procedures that accompany police officers placing their knee on citizens and as long as Confederate statues are taken down but racist beliefs remain erect in the minds and hearts of certain citizens and systems, we will not obtain the reform and reparations needed for lasting and authentic change.

How can we honor Juneteenth?

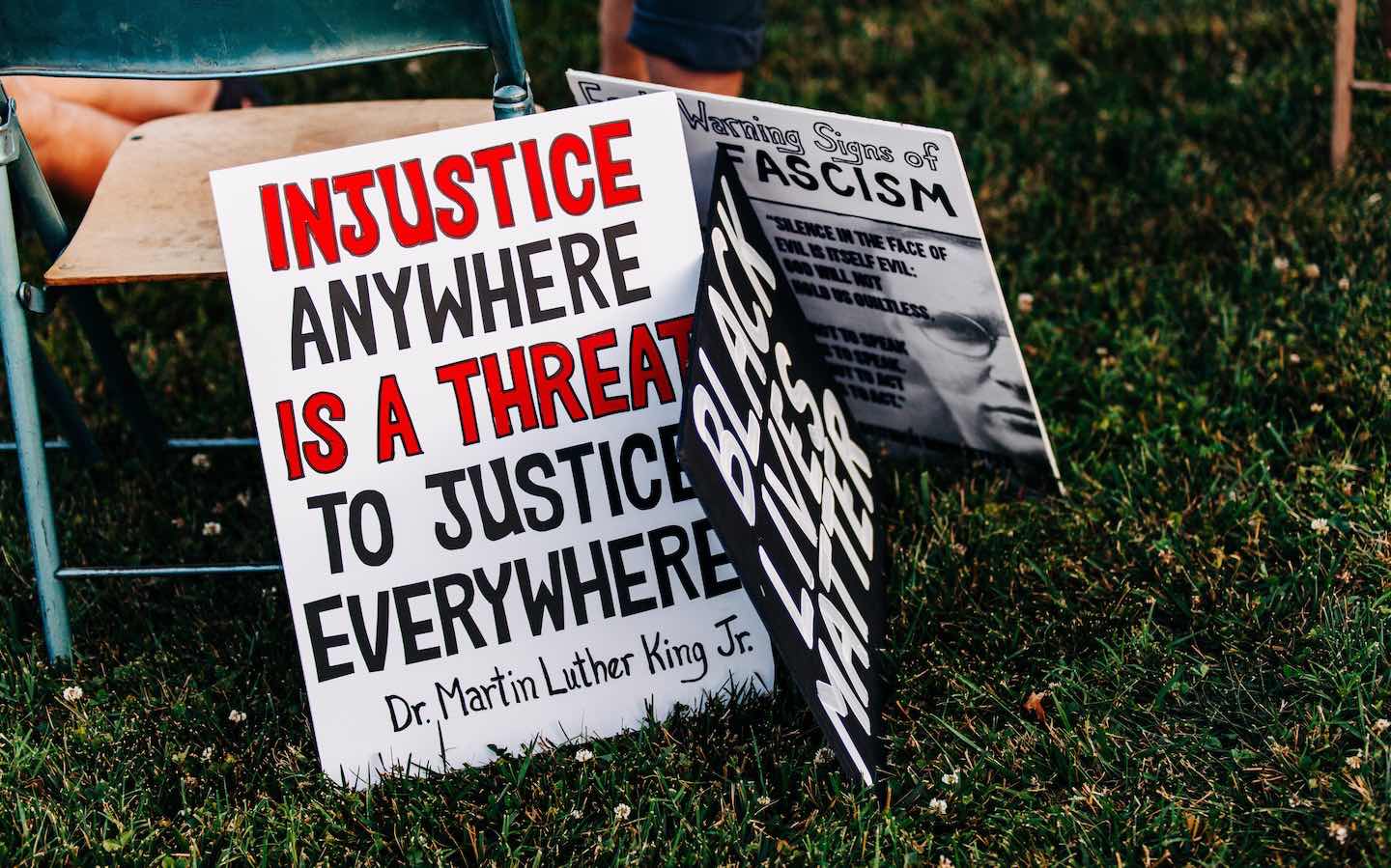

One thing that students (and I would add faculty, staff and the administration) can do to put the University’s social justice mission into action in honor of Juneteenth is to realize that “social justice” is more than a moment; it’s a movement. It's more than a #hashtag or tagline, it’s a lifestyle. Social justice is more than a destination — it’s a process and it starts right where you are. You do not need a huge platform or arena. You can use where you are to assert that changes and reform need to occur.

Social justice is more than protesting and signing petitions. That’s effective, yes, and it also needs a changing of mindset, an acknowledgment by allies of privilege and an understanding of language, how some things we say also reinforce oppression and disenfranchisement.

In honor of Juneteenth, where enslaved Africans did not know of their freedom until two and a half years after the fact, we have an obligation to inform ourselves and others of actions we need to take and language we need to embrace in a timely and accurate fashion. We need to know about our elected officials NOW. We need to know what public bills are pending NOW. We need to know how our studies, assignments and assessments in our classrooms demonstrate historical and inclusive curriculum of African Americans NOW.

We no longer need to wait until February for Black History Month to see, acknowledge and celebrate African Americans and their accomplishments. We can do it with inspiration and intentionality NOW.

Natasha L. Robinson, Esq., Lecturer in the Department of Government, Law and Justice, has been a licensed attorney specializing in the area of criminal defense for twenty years, having worked as an assistant public defender for the Law Office of Cook County Public Defender for twelve years. While an assistant public defender, Natasha noticed several trends that left a negative impact on her clients. Her passion to provide information and education to others (young people in particular) about criminal justice and the legal system led her from the courtroom to the classroom. Natasha went on to be the head of the Law and Public Safety Academy, a four-year pre-law honors program at Hirsch High School and Al Raby School for Community and Environment, both of which are Chicago Public High Schools.

As a lecturer, Natasha brings her passion for law and education to higher education, teaching students about criminal justice and creating professional connections for students who wish to pursue criminal justice in graduate courses or in careers. Natasha’s aim is to educate students about the theory and everyday practice of criminal justice as well as to showcase “law in action,” aligning course work and service to the social justice mission of Roosevelt University.